Will it get worse? Should I have surgery? How long can I live with it? These are some of the questions I want to address about mitral valve regurgitation, one of the most common heart valve problems. But first, some cardiac geography.

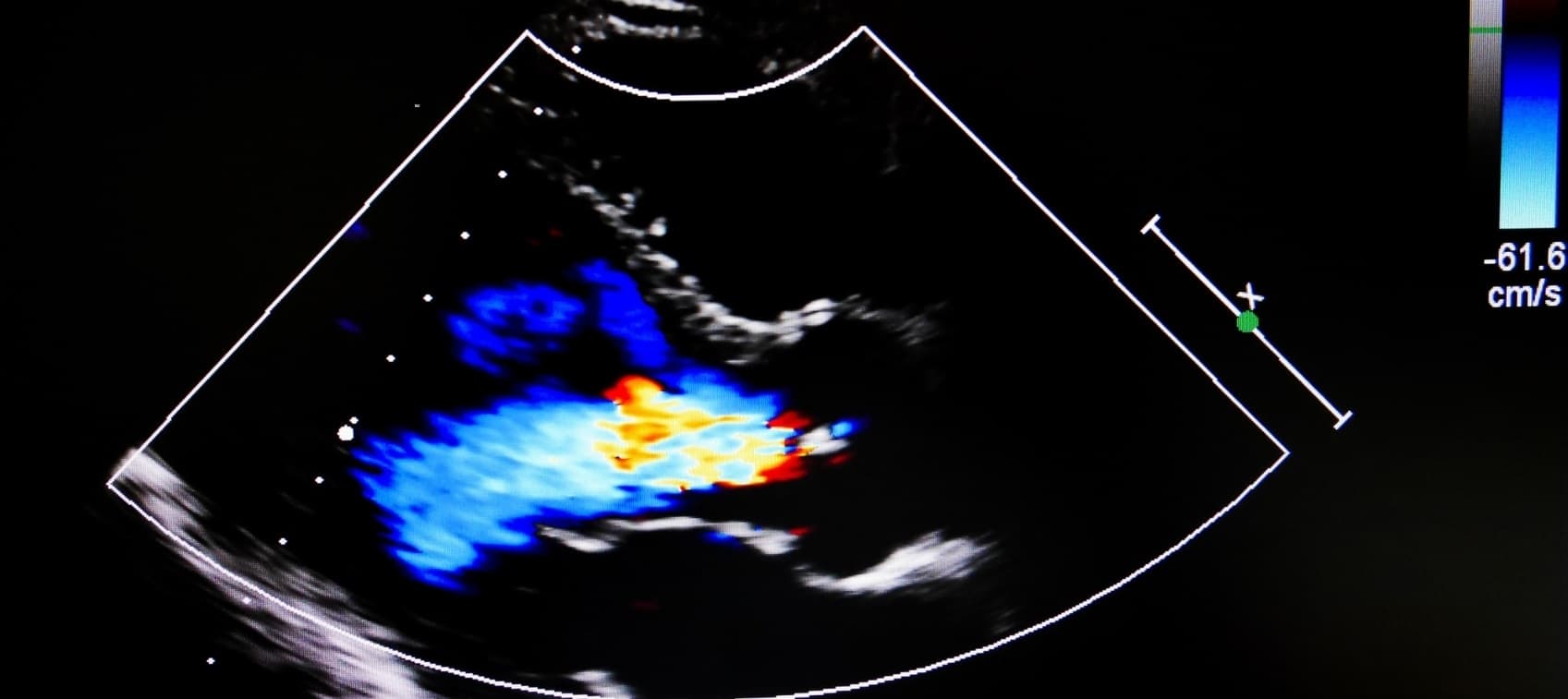

The mitral valve, one of the four valves separating the chambers of your heart, is located between the left atrium (the top chamber) and the left ventricle (the lower chamber). Oxygenated blood flows from the lungs into the left atrium, and then through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the ventricle, blood is pumped out through the aorta and into the rest of the body.

Mitral valve regurgitation—also called mitral insufficiency or incompetence—occurs when the valve doesn't close as tightly as it should and some of the blood spills backward into the atrium. This reduces the amount of blood pumped out into the body with each beat.

Symptoms of Mitral Valve Regurgitation

If the condition is mild and the backward leak of blood is small—as it is in most cases—mitral valve regurgitation causes no symptoms or problems. You wouldn’t even know you had it unless it was picked up on an echocardiogram.

If it progresses, however, more blood spills backwards through the leaky mitral valve, and the ventricle has to pump harder to meet the body’s demands for oxygenated blood. This places extra strain on the heart and, over time, may cause changes in the heart such as enlargement and weakening of the left ventricle. Think of the analogy of saltwater taffy—if you stretch it too far, it won’t snap back.

That’s when you may notice symptoms like fatigue and shortness of breath, especially with activity. In severe cases, these symptoms may worsen and be compounded by swelling of the feet or ankles, arrhythmias, and other signs of heart failure.

Although symptoms occasionally come on rapidly, mitral valve regurgitation is usually mild, progresses very slowly, and is symptom-free.

What Are the Risk Factors for Mitral Valve Regurgitation?

Many people older than 55 have some degree of mild mitral valve regurgitation due to age-related deterioration of the heart valves. Damage to the heart valves or muscle caused by heart attack, cardiomyopathy, congenital defects, trauma, and infections such as rheumatic fever and endocarditis also increases risk.

Another condition, called mitral valve prolapse, is often accompanied by slight mitral regurgitation. Although some patients with this common valve abnormality develop more significant leakage, that is the exception rather than the rule. In most cases, mitral valve prolapse does not lead to severe regurgitation.

What Causes Mitral Valve Regurgitation To Get Worse?

Hypertension most certainly worsens this condition. High blood pressure puts a strain on the left ventricle, making it work harder. If there is slight leakage of the mitral valve, increased pressure can accentuate it—and the higher the systolic pressure (the first number in blood pressure readings), the more blood that can leak backward into the atrium.

For anyone with hypertension who also has mitral valve regurgitation, lowering the blood pressure is strongly advised—it is the most important preventive measure you can take.

Can Mitral Valve Regurgitation Cause High Blood Pressure?

The real concern, as noted above, is not that mitral valve regurgitation causes hypertension, but that hypertension can make mitral regurgitation worse.

That said, because long-standing untreated mitral regurgitation increases pressure in the left atrium, it may eventually lead to pulmonary hypertension. This rare type of hypertension, which affects the pulmonary arteries in the lungs, is often chronic and progressive, and if left untreated, has a poor prognosis.

Can Mitral Valve Regurgitation Cause Atrial Fibrillation?

Yes! Atrial fibrillation is a common consequence of progressive mitral valve regurgitation. The resultant stretching, enlargement, and other abnormalities of the left atrium could be a harbinger of atrial ectopic activity—premature beats due to abnormalities in the heart’s electrical system—and may progress to atrial fibrillation.

Does Mitral Valve Regurgitation Cause Anemia?

In all my years as a clinical cardiologist, I have not seen mitral regurgitation-related anemia. Diminished cardiac output can lead to renal insufficiency (impaired kidney function) over time, and this could result in a chronic anemia-like situation. It is possible, but very rare.

How Long Can You Live With Mitral Valve Regurgitation?

I’ve had patients live into their 90s and even 100s with mitral valve regurgitation—it’s the best-tolerated heart valve problem. Unfortunately, it occasionally progresses, becomes symptomatic, and leads to complications such as heart failure that shorten life expectancy.

Most patients, however, have mild cases, do not require significant medical intervention, and lead normal lives. The most important thing is to follow up with your physician on a routine basis and have serial echocardiograms to monitor your progress.

When Does Mitral Valve Regurgitation Require Surgery?

That’s the $64,000 question. If you have a leaky mitral valve and your heart is somewhat enlarged but your quality of life is pretty good, I would say don't have valve repair or replacement surgery. Get serious about lifestyle changes and other interventions to control your blood pressure and improve your cardiovascular health. I have recommended this approach to many, many patients, and most of them have been able to delay surgery for decades—they never needed it!

The decision to have surgery boils down to quality of life. If your symptoms are severe and surgery could improve your quality of life and reduce your risk of heart failure and other complications, then go for it. Be aware, however, that if your left ventricle is significantly enlarged, replacing the valve may not have a substantial effect.

Managing Mitral Valve Regurgitation

I’ve found that this condition responds beautifully to an integrative approach, which you can discuss with your doctor. Using conventional and alternative therapies, most people can slow progression, improve symptoms, and avoid surgery:

- Control your blood pressure with sodium restriction and other diet changes, stress management, targeted supplements, and medications, if needed.

- Maintain your optimal weight with a heart-healthy diet and exercise. There are no exercise restrictions for patients with run-of-the-mill mitral valve regurgitation.

- Manage coexisting conditions such as atrial fibrillation with natural and pharmaceutical therapies.

- Take supplements for a healthy heart, including coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), carnitine, D-ribose, and magnesium to help build energy substrates in the heart; omega-3 fatty acids to reduce inflammation; and antioxidants to protect against oxidative stress.

- Follow up with your doctor for periodic echocardiograms.